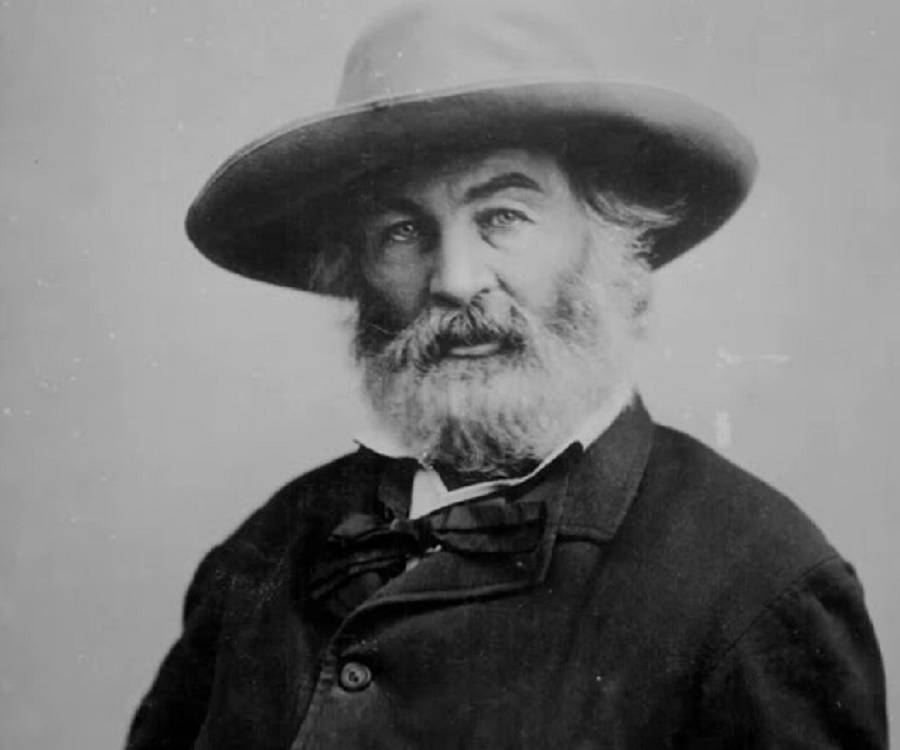

One is left to wonder whether this quintessentially 19th-century American poet would be tickled to be the fearless bearded leader of our century's sordid revolutions. Vendler has her doubts, and so do I.

And yet, I find it remarkable how transplantable the words of Whitman are to revolutionary sympathies. Poets and other writers writing in the late 19th-century were writing towards the generosities of their fellow men, towards a certain hope for humanity—and how interesting too that the American Civil War was taking place at the same time, this a time where generosities and hopes were particularly important to the ethos of the American Union. It is no surprise then that those writers whose literatures were especially present during that war (Whitman, Melville, Emerson) are ones who today remain so quotable.

The idea of superimposing aesthetics and moral codes of the past over our own is not necessarily a mistake, I don't think. It isn't right as it can unnecessarily open doors to hubris and misrepresentations in art, but deferring completely to one's biography to refute such claims just isn't exciting to me. And to be clear, I'm not saying that Vendler is doing this. She actually is quite fair in her assessment of Williams' book. But I'm interested here in the power of history in literature, current and past. How change occurs in one lens, and doesn't in another.

Emerson talks about the "immobilities" and "absence" of "elasticity" in art in his essay Experience ; later, he talks about time and human equivalence, how five minutes of time today are, no matter what, equal to five minutes of time one hundred years ago. I balked, it's true, at this idea that art is not flexible, and also that time is qualified, well, by time and time alone—not exactly poetic. But if we begin to think of "Guernica" or "Moby Dick," the frameworks remain intact; that five minutes of time when removed from context is still five minutes of time that passes. War provides a framework. Industry provides a framework. Vendler talks in the end about how ethics too, along with variables like landscape, anecdote, and history, is a subordinate factor to the poetry.

I think this is what compels us to presume certain liberties in our American icons. Just as Ginsberg searched the post-industrialized supermarket for the forefather of American poetry in a place as unlikely for Whitman as California, it remains understandable for one of our famed contemporaries to participate in that same imaginative search for the Whitman in our own questionable history.

No comments:

Post a Comment